The Pāṇḍavas were also favored by their military teacher, Kṛpa. Kṛpa was the noble-minded son of a brahmin who had adopted the warriors profession. He told the princes his history. His father, a rishi named Gautama, had been engaged in fierce austerities and weaponry practice, for which he had an affinity. Gautama’s asceticism and martial skills were so great that even Indra feared the rishi might exceed him in power and usurp his position in heaven. That anxious god therefore sent a beautiful Apsarā, a heavenly nymph, to divert Gautama from his asceticism. When the rishi saw the semi-clad Apsarā before him, he lost control of his mind and semen fell from his body. It landed in a clump of heath, and from it two children were born. Gautama fled after seeing the Apsarā, not realizing that he had miraculously sired the children. Soon after he left, some of the king’s soldiers found the two babies and brought them into Hastināpura.

Some time later, Gautama, understanding everything by his mystic power, came to the city and explained to the king what had happened. The rishi taught his son all his military skills and in time Kṛpa became the teacher of the princes.

Bhīṣma was pleased with Kṛpa’s teaching. The boys were becoming highly adept at weaponry. But he wanted them to learn the secrets of the celestial weapons as well so that they would be unmatched in warfare. Kṛpa did not have this knowledge. Bhīṣma had therefore been searching for a suitable teacher to take the princes further in military science. None he had seen had impressed him as qualified to train the princes.

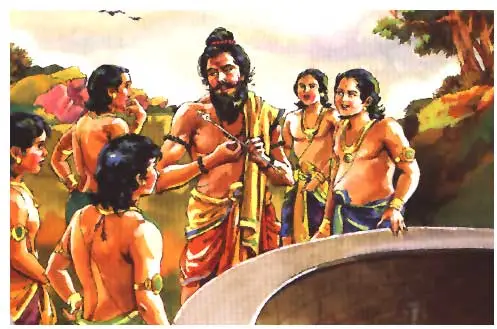

Then one day the boys ran to Bhīṣma with a strange tale to tell. They had been out playing ball in the woods. The ball fell into a deep, dry well and the princes could not recover it. As they stood by the well looking at one another in embarrassment, a dark man approached them. He was a brahmin, appearing emaciated and poor, but with a bright effulgence and glowing eyes. The princes surrounded the brahmin and asked if he could help them. Smiling a little, the brahmin said, “Shame upon your prowess as warriors. What use is your skill in arms if you cannot even retrieve a lost ball? If you give me a meal I’ll recover the ball, as well as this ring of mine.”

He then took off his ring and threw it into the well. Yudhiṣṭhira said to him, “O brahmin, if you can recover the ball and the ring, then, with Kṛpa’s permission, we shall ensure that you are maintained for your whole life.”

The brahmin took a handful of long grasses and said, “Watch as I invest these grasses with the power of weapons. With these I shall pierce the ball and bring it to the surface.” He chanted mantras and threw the grasses one by one into the well. The first one pierced the ball and each subsequent blade he threw stuck into the last one to form a long chain. The brahmin then pulled the ball out of the well.

The princes were astonished. “This is truly wonderful, but let us now see you raise the ring.”

The brahmin borrowed one of the princes’ bows and shot a single sharp-pointed arrow into the well. With it, he brought up the ring, caught on the arrow’s head. The princes crowded around him and asked him to reveal his identity. They had never seen such skill. The brahmin told them to go to Bhīṣma and describe what they had seen. He would know his identity. The brahmin said he would wait there until they returned.

Thus the boys ran back to the city and told Bhīṣma everything. When he heard the tale his eyes shone with joy. Surely this could only be Droṇa, the disciple of his own martial teacher, Paraśurāma. Bhīṣma had heard much about Droṇa from the rishis. This was certainly providential. The princes could have no better teacher. Bhīṣma went in person with the boys to see the brahmin. Finding as he had suspected that it was Droṇa, Bhīṣma immediately offered him the position of a royal teacher. Droṇa accepted and went to Hastināpura with Bhīṣma.

When they were back in the city Bhīṣma had Droṇa tell everyone of his history. Droṇa looked around at the eager-faced princes. They wanted to know everything about this unusual brahmin. He was the son of Bharadvaja, the all-powerful rishi who had dwelt for thousands of years in the deep forest and who, not long ago, had finally ascended to heaven. Although he too was a brahmin, Droṇa was inclined toward martial arts. While living in his father’s hermitage he had learned the science of arms from Agnivesha, another powerful rishi. He had also received knowledge of the celestial weapons from the great Paraśurāma. Despite having such great learning, however, Droṇa remained a poverty-stricken brahmin. He could hardly maintain his family. Thus he had been on his way to Hastināpura hoping to be engaged as the princes’ teacher.

Bhīṣma said, “Make your residence here in the city. You shall enjoy every luxury along with the Kurus. Indeed the Kurus are at your command. Whatever wealth, kingdoms and followers that belong to our house are also yours. O best of brahmins, it is our good fortune you have arrived here.”

Droṇa was given a large, well-furnished house, stocked with everything enjoyable and attended by many servants. He then brought his wife and son to Hastināpura to live among the Kurus with him, and he accepted both the Pāṇḍavas and Kauravas as his disciples.

Droṇa taught the princes everything he knew about weaponry. The boys practiced every day from dawn till dusk. As the news of his martial school spread, princes from other kingdoms also came to learn from the famous Droṇa. The Vrishnis, the Andhakas and other famous and powerful dynasties sent their princes to Droṇa and he accepted them all as his pupils. Soon Droṇa had thousands of students.

Among all the boys Arjuna excelled at his lessons. He remained always at Droṇa’s side, eager to learn any little skill or extra tips. His ability, speed, perseverance and determination were unequalled by the other princes. Arjuna became foremost; Droṇa felt none could match his skills.

Out of his natural fatherly affection, Droṇa also wished to impart extra lessons to his own son, Aśvatthāmā. He gave all the princes narrow-mouthed water pots and asked them to fill them at the river, but to his own son he gave a wide-mouthed pot so he could return first and receive extra teaching. Arjuna realized Droṇa’s intentions and he filled his own pot with a celestial water weapon, and thus returned before Aśvatthāmā. Droṇa smiled when he saw Arjuna’s determination. His desire to learn from his preceptor was beyond compare. Arjuna always carefully worshipped Droṇa and was attentive to his every command. Because of his devotion to studies and his guru, he became Droṇa’s favorite student.

Once Arjuna was eating his meal at night. Suddenly the lamp blew out. It was pitch black. Arjuna continued to eat as if nothing had happened. As he did so, he realized that simply by habit he was able to place the food in his mouth, although he could see nothing in the darkness. He then began to practice with his bow and arrows in the night, aiming at invisible targets. When Droṇa saw this dedication he was overjoyed. He told Arjuna, “I shall make you unmatched upon the earth. No warrior shall be your equal.”

Droṇa then taught Arjuna how to fight on horseback, on an elephant, from chariots and on the ground. He showed him all the skills of fighting with clubs, swords, lances, spears and darts, as well as many other types of weapons. Droṇa also taught him how to contend with any number of warriors fighting at once. As Droṇa promised, his skill soon became without compare on earth.

One day, a prince of the Nishada tribe of forest dwellers asked Droṇa to teach him. His name was Ekalavya. Droṇa replied that his school was only for kings and princes. Ekalavya went away dismayed. Strongly desiring greatness in martial sciences, he practiced alone in the woods. He built an effigy of Droṇa and worshipped him daily, praying to him for skills at weaponry. Gradually he became an expert archer.

Once, as he was practicing, a dog began to bark loudly and disturb him. Immediately he released seven arrows, even without seeing the dog, and sealed the animal’s mouth.

It so happened that Arjuna and his brothers were in the woods at the time and they saw the dog, its mouth closed with arrows. They marvelled at this and wondered who was responsible for such a feat. Soon they came upon Ekalavya and, seeing the dark-skinned Nishada, smeared with filth, his hair matted, they asked him who he was. He replied, “I am Ekalavya of the Nishadas, a disciple of Droṇa. I practice alone in these woods with a desire to become the best of archers.”

Arjuna was seized with anxiety. This boy posed himself as a disciple of Droṇa, even though he had been rejected by him. It was completely against all religious principles. No one could claim to be a disciple of a guru unless he was accepted as such by that teacher. And Ekalavya had even flouted his so-called guru’s order. Droṇa had told Ekalavya that he could not be his student. The Nishadha clearly had no devotion to Droṇa, despite his outward show of dedication, as he did not accept Droṇa’s order. How then could he be allowed to present himself as Droṇa’s disciple–and practically his best one at that? His skills were astonishing, but they had been gained by disobedience. Arjuna went at once to his guru to inform him.

Droṇa was immediately perturbed. He remembered dismissing Ekalavya and he could understand Arjuna’s intimations and anxiety. After thinking for some moments he replied, “Come with me, Arjuna. We shall see today what caliber of disciple is this prince.”

Droṇa went at once with Arjuna into the woods. When Ekalavya saw them approach he fell to the ground and touched Droṇa’s feet. Then he stood before Droṇa with folded palms, saying, “My lord, I am your disciple. Please order me as you will.”

Droṇa looked with surprise at Ekalavya and at his own effigy nearby. He recalled the day the forest prince had come to him and been turned away. Droṇa was angered that he was now claiming to be his student. The Kuru preceptor had not desired to impart any martial skills to Ekalavya. Generally the lower caste tribespeople lacked the virtuous qualities of royalty, and they did not follow the Vedic religion. To give a low-class man great martial power could be dangerous. Droṇa had been especially concerned about Ekalavya, as the Nishadha tribe did not cooperate with the Kuru’s virtuous rule. Droṇa would not accept any princes into his school if they belonged to races antagonistic to the Kurus.

Droṇa stood thinking for some time. His first assessment of Ekalavya had obviously been correct. The Nishadha had shown himself to be lacking in virtue by falsely posing as his disciple. Clearly he desired only to be great, known as a student of the famous teacher, but not to actually obey him.

Smiling a little, Droṇa said to the Nishada, “O hero, if you really wish to be my disciple then you must give me some dakṣiṇa. The disciple should be prepared to give anything to his guru. Therefore I ask you to give me your right thumb.”

Droṇa knew that this was asking a lot from Ekalavya. The loss of his thumb would impair his skill at bowmanship. But if he wanted to be known as Droṇa’s disciple, he could not refuse. Droṇa also wanted to show that one cannot please his teacher and achieve perfection by dishonest means. By taking Ekalavya’s thumb, he was also removing any threat he or his race might pose to the Kurus.

Droṇa looked expectantly at the Nishadha prince. Ekalavya immediately took out his hunting knife. Although he had been unable to accept Droṇa’s first order, the prince did not want to be considered at fault for failing to give dakṣiṇa to his guru. And he knew that all his knowledge and skills would be nullified if he refused Droṇa’s request. Without the least hesitation, he cut off his thumb and handed it to Droṇa.

Droṇa took the thumb and thanked the prince. Raising his hand in blessing he turned and walked quickly away, followed by a relieved Arjuna. With his firm action, Droṇa had clearly upheld religious principles.

Reference:-https://vedabase.io/en/library/mbk/1/4/