King Daśaratha paced his palace balcony. His handsome brow was furrowed. In a pensive mood, he surveyed the scene around him. People thronged the inner courtyard below. Feudal kings and princes came with their retinues to pay tribute. From his seventh-story terrace Daśaratha could see much of his city, which stretched to the horizon in all directions. Crowds of citizens moved along the well-planned roads, which were interspersed with mango groves and orchards. The broad central highway, built entirely of red stone, ran the full hundred-mile length of the city. Large white mansions lined that road, with many-colored pennants waving in the breeze on their roofs. The road was sprinkled with perfumed water and strewn with flowers. Above the city the king could see the golden airplanes of Apsarās, the consorts of the gods.

Looking out over his capital, Ayodhya, Daśaratha was plunged in an ocean of anguish. He entered the palace and walked slowly towards his inner chambers. As he descended the wide marble stairways, he heard his priests chanting sacred Sanskrit texts. The sound of mantras mingled with that of drums and lutes being beautifully played by royal musicians. Even that sound, which normally gave him so much joy, could not placate him.

The king sat lost in thought. He looked at the exquisite carvings of the gods lining his walls. All his life he had done so much to please those deities. Once he had even gone into battle against the celestial demons on their behalf. Surely they would help him now. Daśaratha silently prayed to them.

While the king sat absorbed in his thoughts and prayers, a messenger came telling him that his chief priest Vasiṣṭha was now present in the assembly hall. Daśaratha had been waiting for this news. He rose up, and with the gait of a powerful lion went along the wide palace passageways, his large sword swinging at his side and his gold ornaments jangling as he walked.

Near to the hall he was joined by his chief ministers. All of them were heroes who had been tried in battle, and all were learned and wise. The state ran smoothly under their expert administration. There were no citizens without employment and no criminals left unchecked. The ministers were devoted to Daśaratha’s service, and as they walked they considered the problem facing the king.

Flanked by his bodyguards and ministers, Daśaratha entered his great hall. It vied in splendor with the assembly hall of Indra, the king of the gods. Massive marble pillars rose up to a roof which seemed to reach the sky. Balconies of alabaster and coral, worked with gold filigree, were gradually tiered all around the hall. Along the balconies were gold seats spread with white cushions. Large silk tapestries depicting the pastimes of the gods hung from the walls, which were lined with lapis lazuli and encrusted with jewels. The air was filled with the scent of incense. In the center of the hall sat numerous priests who continuously chanted prayers from the ancient scriptures, invoking the presence of deities. The great megha drum resounded deeply as Daśaratha strode towards his seat. Everyone stood and there was a cry of “Victory! All glories to Emperor Daśaratha!” The king, appearing like a god, took his seat on a large throne of refined gold bedecked with brilliant celestial gems.

A hush descended on the assembly as Daśaratha prepared to speak. Everyone sat in expectation. The citizens knew of the king’s worry; they loved him like a father and shared his anxiety. They were grouped in the hall according to their class. At the front were the Brahmins, wearing simple cloth and holding their waterpots and prayer beads. On one side sat the warriors, their powerful bodies clad in silks and gold ornaments, with long swords hanging from their belts. Near to them were the tradespeople in their colorful dress, and behind them were the servants and workers, also beautifully adorned. All social classes were represented in that assembly.

Daśaratha looked around the hall, smiling affectionately at everyone. Although the king was preoccupied with his worry, no one could detect in him any negligence or laxity in his duties. Seeing him smiling at them, the people felt reassured that Daśaratha would find a solution to his problem. They sat awaiting his speech.

Placing his hand on his golden scepter, the king turned to his chief priest Vasiṣṭha, who sat on a raised seat near the throne. With a powerful voice that boomed around the hall, Daśaratha addressed the priest. “I have called this assembly to settle a great worry of mine. As you know, this wide earth has for a long time been held under the sway of victorious kings in my line. O jewel among sages, is that glorious history about to end? What can I do to ensure that our proud lineage will continue?”

Daśaratha was perturbed that he had no son. Having ruled as the undisputed emperor of the earth for thousands of years, his retirement was now approaching; but there was no one to succeed him. Somehow, none of his wives had given birth to a son. The king had called for a full assembly to propose an idea he was considering. He needed the approval of the Brahmins and he wanted the consent of his people. Daśaratha looked anxiously at Vasiṣṭha, who was both his priest and preceptor. “O learned one, you know well the perils that attend a kingdom bereft of a monarch. How can I retire to the forest leaving this world without a protector?”

Vasiṣṭha sat surrounded by many other Brahmin sages. His hand rested upon his staff as he listened to Daśaratha. The sun shone through the carved lattice windows of the hall, covering the king with golden light. Vasiṣṭha, shining with his own mystic power, appeared like a second sun as he replied to the king. “O emperor, I have no doubt that you will soon be blessed with a powerful son who can succeed you. Not long ago I heard this told by Sanat Kumar, the immortal sage who roams the universe. A divine arrangement is being worked by the gods for your everlasting benefit.”

The king felt joy to hear his priest’s words. Like his forebears before him, Daśaratha had religiously pursued his duties as emperor. Under his benevolent rule, the world enjoyed prosperity and peace. The king desired not only the immediate material enjoyment of his people but their spiritual well-being as well. He kept everyone on the path of piety and truth, leading them towards freedom from the cycle of birth and death. Seeing all the people as his own children, he was concerned that their happiness would continue after his retirement. He spoke again. “I have been considering the performance of a horse sacrifice for the pleasure of the gods and Viṣṇu. O noble sages, will this be successful? Can I satisfy the Lord in this way and thereby attain my desired end?”

Daśaratha knew that nothing could be achieved unless Viṣṇu, the Supreme Lord, was pleased. Although they controlled the universe, the other gods were but Viṣṇu’s agents. Many times in the past the king’s ancestors had performed great sacrifices for satisfying the Lord and achieving their purposes. The king now considered this to be his only means of deliverance. He looked hopefully at Vasiṣṭha, who had been speaking with the other sages at his side. Turning towards the king Vasiṣṭha said, “We are in agreement, O tiger among men. Let the sacrifice proceed! We shall immediately prepare a ground on the banks of the Sarayu. You will certainly get a son by this method.”

The assembly erupted with joyful shouts. Everywhere were cries of “Let it be so! Let the sacrifice proceed!”

The king, his eyes grown wide with delight as he anticipated the fulfillment of his desire, said to Vasiṣṭha, “Let the preparations begin today. Protected by four hundred of my best warriors, the sacrificial horse will roam the globe before returning for the sacrifice.”

After Daśaratha had issued all necessary instructions the assembly was dismissed and the king retired to his inner chambers. Together with his wives, he worshipped Viṣṇu and the gods, praying that his sacrifice would succeed.

* * *

The whole city of Ayodhya was filled with excitement as the news of the king’s sacrifice spread. In the large public squares minstrels sang songs recounting the exploits of heroes in Daśaratha’s line, while troupes of female dancers depicted the tales with precise and beautiful gestures. The temples became crowded with joyful people praying for the success of Daśaratha’s sacrifice. From the balconies of

houses lining the wide avenues, wealthy people threw down gems for the Brahmins and the jewels sparkled brightly on the clean, paved roads. The city resonated with the sound of lutes, trumpets and kettledrums. Augmenting the music was the chanting of Brahmins reciting the holy scriptures. With flags and pennants flying, festoons hanging between the houses and flowers strewn everywhere, Ayodhya had the appearance of a festival held by the gods in heaven.

The priests of Ayodhya set about preparing for the sacrifice. Selecting and consecrating a purebred horse which was free from any blemish, they released it to range freely across the country. As it traveled, it was followed and protected by four hundred powerful generals from the king’s army. According to the ritual, wherever the horse went, the residing rulers were called upon to attend the sacrifice and pay homage to Daśaratha. Anyone refusing would be immediately challenged to a fight. If they were not subjugated, then the sacrifice could not proceed. None, however, wished the emperor any ill. The horse came back to Ayodhya without incident at the end of one year.

Seeing the horse returned, Daśaratha called Vasiṣṭha. He touched his guru’s feet and asked him with all humility, “O holy one, if you deem it fit, please now commence the sacrifice. You are my dearest friend as well as my guru. Indeed, you are a highly exalted soul. Fully depending on you, I am confident of the sacrifice’s outcome.”

After assuring the king, Vasiṣṭha spoke with the priests, instructing them to have the sacrificial arena built. Chief among them was Rishwashringa, a powerful Brahmin who had come from the kingdom of Aṅga. It had long ago been prophesied that Rishwashringa would help Daśaratha obtain progeny. Along with Vasiṣṭa, he took charge of the arrangements for the sacrifice.

Vasiṣṭa ordered that many white marble palaces be constructed for the monarchs who would attend. The very best food and drink was made available, and actors and dancers came to entertain the guests. Horse stables, elephant stalls and vast dormitories to accommodate thousands of people were built. Vasiṣṭha instructed the king’s ministers, “Everyone should have whatever they desire. Take care that no one is disrespected at any time, even under the impulse of passion or anger.”

Vasiṣṭha spoke to the king’s charioteer and minister, Sumantra, who was especially close to Daśaratha. “We have invited kings from all over the globe. On behalf of the emperor you should personally ensure that they are all properly received. Take particular care of the celebrated king Janaka, the heroic and truthful ruler of Mithila. With my inner vision I can see that he will in the future become intimately related to our house.”

Soon many kings came to Ayodhya bearing valuable gifts of jewels, pearls, clothing and golden ornaments. Upon their arrival they in turn were offered gifts at Vasiṣṭha’s command, who had instructed his assistants, “Give freely to all. No gift should ever be made with disrespect or irreverence, for such begrudging gifts will doubtlessly bring ruin to the giver.”

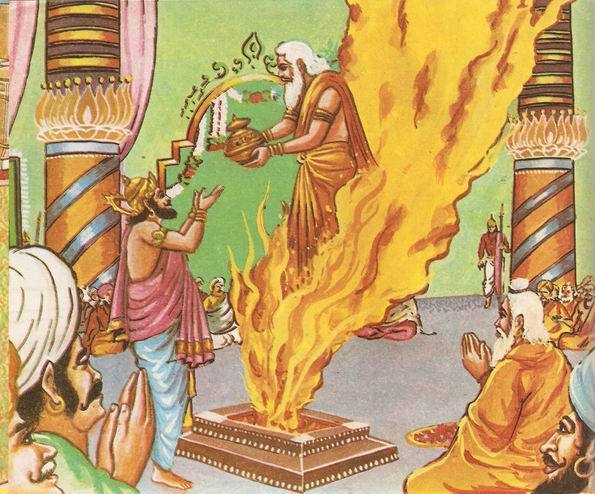

The royal astrologers ascertained the most favorable day for the commencement of the sacrifice. Daśaratha, headed by Vasiṣṭha and Rishwashringa, and accompanied by his three wives, then came to the sacrificial compound, which resembled an assembly of the gods. Many fires blazed, each dedicated to a different deity and attended by numerous Brahmins. The great compound was crowded with sages absorbed in prayer and meditation. On all sides stood warriors equipped with every kind of weapon, fully alert to any danger. The king sat surrounded by Brahmins, who consecrated him for the sacrifice. He and his wives made offerings into the fires and joined in the chanting of prayers.

After some days the horse was brought before the sacrificial fire dedicated to Viṣṇu. Learned priests constantly poured into it oblations of clarified butter along with handfuls of grains. Taking the horse by its reins, Vasiṣṭa uttered a powerful mantra and the animal fell unconscious. It was immediately placed upon the fire. As the horse was consumed by the blazing fire, those with divine vision saw the soul of the creature rise from the fire, glowing brilliantly, and ascend towards heaven.

As the sacrifice concluded, Daśaratha was delighted. He said to the priests, “According to the ordinance it is fitting that I now bestow upon you proper charity. Therefore, O holy ones, take this entire earth as a gift. This is the only appropriate offering for great souls like yourselves.”

The priests replied, “You alone are able to protect this earth with its countless people. As ascetics we having nothing to do with the world, nor are we able to maintain it; therefore we leave it with you, O monarch.”

The priests quickly raised up the king. They understood the scriptural injunction to which the king alluded. “If it so pleases you, then you may give to us a little wealth. We have no use for the earth.”

The king distributed to the Brahmins hundreds of millions of gold and silver coins, as well as millions of milk-bearing cows. He supplied tens of thousands of Brahmins present at that sacrifice with enough wealth to last their entire lives.

Vasiṣṭha and Rishwashringa then arranged for one final ritual to be performed. They called the gods by name to come and accept the sacrificial offerings made to them. The celestial smoke from the offerings, sanctified by Vedic mantras, rose upwards to the skies and was received by the gods. With the universal creator Brahmā at their head, they personally assembled in sky above Daśaratha’s sacrificial compound. Unseen by everyone, the gods began to address Brahmā:

Brahmā, was concerned that his boon to Rāvaṇa had created such problems, listened as Indra, on behalf of the gods, continued: “Rāvaṇa sought invincibility but did not ask for immunity against humans, whom he considered of no consequence. Thus his death must come at the hands of a human. Please, therefore, beseech the Lord to appear as Daśaratha’s son.”

Although Rāvaṇa could still be killed by a human, the gods knew that no ordinary man could slay him. It could only be done by the all-powerful Viṣṇu himself, if he came to the earth as a man. And here was the ideal opportunity. The emperor of the earth was praying to Viṣṇu for a powerful son. Surely the Lord would consent to appear in Daśaratha’s family, especially if Brahmā, Viṣṇu’s devoted servant, also prayed to him to appear.

Brahmā assented to the gods’ request. He knew that the time for the Lord’s appearance had come. Seated in meditation, Brahmā thought of the Lord within his heart. At that moment Viṣṇu appeared in the sky. Only the gods saw Him as He descended upon the back of His eagle carrier, Garuḍa. His beautiful body was blackish and He shone with a brilliant luster. He was dressed in yellow silk with a garland of blue lotuses. A necklace of bright celestial gems hung around His neck. Adorned with numerous gold ornaments and jewels, He held in His four hands a conch shell, a mace, a discus weapon and a lotus flower. Gracefully descending, He sat amid the gods as they worshipped Him with hymns and prayers.

Viṣṇu smiled at the gods. He spoke reassuringly in a voice deep like the rumbling of thunderclouds. “O gods, give up all fear. Along with My own expansions I shall soon be born as four sons of Daśaratha. I Myself shall appear as his eldest son, and My personal weapons will incarnate as My brothers. After annihilating Rāvaṇa and his demon hordes, I will remain on the mortal plane, ruling the globe for eleven thousand years.”

The inconceivable Viṣṇu then disappeared even as he was being worshipped. The gods felt their purpose was accomplished and, after accepting Daśaratha’s offerings, they returned to the heavens.

In the sacrificial compound the rituals were almost over. Daśaratha sat expectantly, hoping for some sign of success. He was apprehensive. If he could not obtain a son by this method, then he would surely be lost. He looked at the blazing fire as the last offerings were being made.

“Please accept my heartfelt welcome, O divine one,” replied the king with his palms joined. “What shall I do for you?”

“By worshipping the gods in sacrifice you have received this reward,” said the messenger. “Take now this ambrosia prepared by the gods which will bestow upon you the offspring you desire. Give it to your wives and through them you will soon secure four celebrated sons.”

Accepting the ambrosia with his head bent low and saying, “So be it,” the king felt a surge of joy as he took the golden vessel, even as a pauper would feel happiness upon suddenly gaining great wealth.

As a mark of respect, the king walked with folded hands around the messenger, who, having discharged his duty, immediately vanished into the fire from which he had appeared. The king stood in amazement holding the bowl. All around him the Brahmins cried out, “Victory! Victory!” After offering his prostrate obeisances to Vasiṣṭha, Daśaratha left the sacrifice along with his wives and returned to his palace.

All those noble wives of the emperor felt honored and immediately ate the ambrosia. In a short time they felt within themselves the presence of powerful offspring. Their minds were enlivened by the divine energy of the children inside their wombs, and they felt elated. Daśaratha, who had at last attained his desired object, felt as delighted as Indra, the king of the gods in heaven.

Reference: Ramayana – Krishna Dharma Das https://www.vedabase.com/en/rkd/1/1