The Pāṇḍavas began to enjoy life in Hastināpura. They sported with the hundred sons of Dhṛtarāṣṭra, who became known as the Kauravas. Pandu’s sons excelled the Kauravas in all areas: in strength, knowledge and prowess with weaponry. Bhīma was especially powerful and he took delight in defeating the Kauravas in sport. They could not equal him in anything. The exuberant Bhīma possessed the indefatigable power of his divine father. At wrestling and fighting he was unapproachable and could easily hold off the attacks of any number of Kauravas. Out of a boyish sense of fun he would often play practical jokes on them, laughing when they became angered and tried futilely to get back at him.

Duryodhana in particular found Bhīma’s antics and power intolerable. As the eldest son of the blind king, Duryodhana had enjoyed the most prestige in the Kuru house. The Kuru elders had carefully raised him and trained him in the kingly arts, thinking of him as the potential future world emperor. Mindful of the omens seen at his birth, the elders were especially careful to teach him moral codes. The prince was both powerful and capable in all areas of weaponry and politics, and was accustomed to being the center of attention in the royal palace since his birth. When the Pāṇḍavas arrived, however, all that changed. Pandu’s sons were gentle, modest and devoted to their elders. They soon became dear to Bhīṣma, Vidura and the other senior Kurus. Their behavior was a welcome change from that of Duryodhana and his brothers, who tended to be self-centered and proud, and often quite arrogant. Duryodhana quickly became envious of his five cousins. His envy grew up like an oil-fed fire when he saw Bhīma’s pranks.

After another day of humiliation at Bhīma’s hands, Duryodhana felt he could take no more. He spoke with Dushashana, the next eldest of the hundred Kauravas. “Dear brother, this Bhīma is a constant thorn in our sides. He challenges all hundred of us at once and throws us about like pieces of straw. We cannot better him at anything. Why, even at eating he humbles us by consuming as much as twenty of us put together. Something has to be done to check his pride.”

Duryodhana’s eyes narrowed as he spoke. His intentions were vicious. The prince was inclined to wicked acts, and he had been spurred on by his uncle Shakuni, who had taken up residence in Hastināpura. The Gandhara prince had been offended by Bhīṣma’s decision to give his sister to the blind Dhṛtarāṣṭra rather than to Pandu. Now he wanted revenge. He involved himself in court intrigues in order to find a way to avenge himself against Bhīṣma. Hurting the Pāṇḍavas, who were obviously dear to Bhīṣma, was one good way. And, of course, he would simultaneously be advancing the cause of his sister’s sons. Duryodhana was a willing accomplice. The boy saw his scheming uncle as a mentor. When Duryodhana had come to him complaining about Bhīma it did not take much to convince him to do something terrible to the Pandava boy.

Duryodhana revealed his heinous plan to Dushashana. “Tomorrow I shall feed Bhīma an enormous poisoned feast. When he falls unconscious after eating I shall bind his limbs and toss him into the Ganges. With Bhīma gone the other brothers are helpless. We can easily deal with them. Thus my claim to the throne will be unchallenged.”

Dushashana smiled in agreement. He too found Bhīma’s behavior intolerable and, like Duryodhana, had also found his own status in the Kuru house diminish since the Pāṇḍavas’ arrival. He put his arm around his brother and the two of them made their way back to their palace, laughing together as they walked the forest path.

The next morning Duryodhana suggested that all the princes go to the river for some water sports. Soon they mounted their shining chariots, which resembled cities and had great wheels which rumbled like thunderclouds as they headed out, sending up clouds of dust. Upon arriving on the river bank, the mighty youths dismounted from their cars, laughing and joking, and entered the large pleasure house Dhṛtarāṣṭra had built for them.

The elegant palace was built of white marble and it stood seven stories high. Many-colored pennants flew from tall golden flagstaffs on its roof. There were dozens of rooms offering every kind of luxury. Each room was tastefully decorated with tapestries, fine paintings, and ivory and coral furnishings, studded with gems and covered with golden cushions. Royal musicians and dancers stood by, ready to entertain the princes, and a hundred of the king’s select force of bodyguards stood ready to protect them.

Once inside Duryhodhana invited everyone to enjoy the great feast he had arranged for them. He led them through the mansion and out into the central gardens. The boys looked with pleasure upon the large ponds filled with red and blue lotuses and surrounded by soft, grassy banks. Crystal waterfalls made tinkling sounds that blended with the singing of brightly colored exotic birds. The heady scent of numerous blossoms filled the air. Fine cushions had been arranged in lines on the grass and many servants stood by, waiting to serve the feast.

Duryodhana chose the seat next to Bhīma. Then he ordered the servants to bring the food. The dishes were exquisite. Duryodhana had personally mixed the poison with the food he had brought to him. He then offered the plate to Bhīma, feigning love and feeding him with his own hand. The guileless Bhīma suspected nothing and he cheerfully consumed his normal amount. Duryodhana rejoiced within as Bhīma hungrily swallowed the poisoned cakes, pies, creams, drinks and other preparations.

When the feast was over, Duryodhana suggested they all go down to the river for sport. The boys raced to the river in great joy. They wrestled and rolled about on the ground, tossing each other into the clear blue water of the river. As usual, Bhīma was the most energetic. The poison did not appear to have affected him. The prince, who stood head and shoulders above his peers, was a peerless wrestler. Anyone who approached him quickly found themselves sailing through the air and landing in the water. Bhīma would then dive in and create huge waves by thrashing his arms. The other princes were then dunked under the waters by the playful Bhīma.

Late in the afternoon the boys began to tire. They came out of the water and dressed themselves in white robes, adorned with gold ornaments. Then they wearily made their way back to the mansion to spend the night.

Bhīma had consumed enough poison to kill a hundred men, but it was not until evening that the wind-god’s son began to feel its effects. As night fell he felt so drowsy that he decided to lay down by the river and rest. Gradually he lapsed into a deep sleep.

When the other princes had gone back to the mansion, Duryodhana saw his opportunity. Along with Dushashana, he bound Bhīma’s arms and legs with strong cords. Looking furtively around, the brothers quickly rolled the unconscious prince into the river.

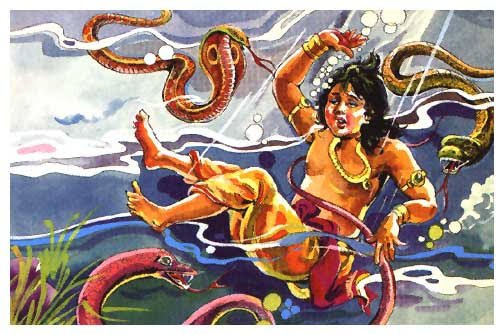

Bhīma sank to the bottom of the river and was carried by underwater currents. The celestial abode of the divine serpent beings, the Nāgas, could be reached through the Ganges, and Bhīma was swept along a mystical path right into their midst. At once the snakes began to bite the human so suddenly arrived among them. Their virulent poison proved to be the antidote to the plant poison Duryodhana had administered. Bhīma slowly came back to his senses as the effect of the poison wore off. He woke to find himself on a strange river bank, surrounded by large serpents baring their fangs.

Bhīma burst the cords binding his limbs. He picked up the snakes and dashed them to the ground. He pressed some into the earth with his feet and hurled others to a distance. Seeing him render dozens of snakes unconscious, the others fled away in terror.

The Nāgas went quickly to their king, Vāsuki. With fearful voices they said, “O king, a human fell among us, bound with cords. Perhaps he had been poisoned, for he was unconscious. When we bit him he regained his senses and overpowered us. You should go to him at once.”

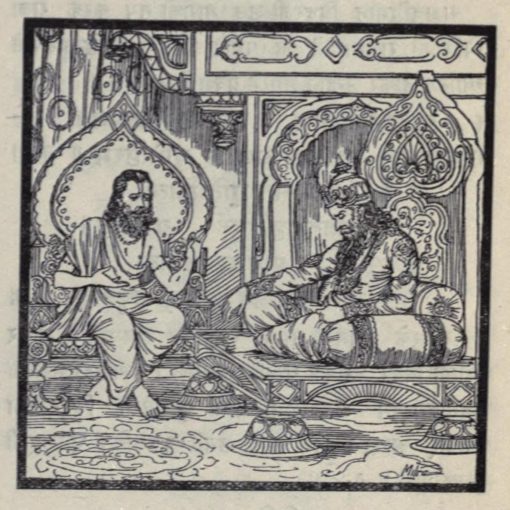

Vāsuki assumed a human form, rose from his bejeweled throne, and walked gracefully out of his palace. Arka, a Nāga chief, went with him. Arka had long ago lived upon the earth in human society. He was Kuntī’s great grandfather and he immediately recognized Bhīma as his great-grandson. Smiling, he introduced himself and embraced the prince.

Seeing this, Vāsuki was pleased and said to Arka, “What service can we render this boy? Let us give him an abundance of gems and gold.”

Arka looked at the powerful Bhīma and replied, “I think this prince would be best served by us if we let him partake of our rasa.”

Vāsuki agreed. Bringing Bhīma back to his palace, he arranged for pots of the ambrosial rasa to be brought for him. This drink was distilled from celestial herbs and by drinking even one pot a man would become permanently endowed with the vigor and strength of a thousand elephants. The Nāgas placed a number of pots in front of Bhīma and invited him to drink. Bhīma sat facing the east and, as he always did before eating or drinking, offered prayers to the Lord. He then lifted one of the large pots of rasa and quaffed it down in one gulp.

The Nāgas watched in amazement as Bhīma drank eight pots of the divine elixir, each in a single draft. Even the most powerful among them would not have been capable of such a feat. After Bhīma had satisfied himself with the rasa, he again felt drowsy. Vāsuki offered him a celestial bed and the prince lay down. He remained in deep sleep for eight days as his body assimilated the rasa. On the ninth day he awoke, feeling strong beyond measure. The Nāgas told him that the rasa had given him the strength of ten thousand elephants. He would now be invincible in battle. Vāsuki told Bhīma to bathe in the nearby sacred waters of the Mandakini, then dress himself in the robes the Nāga king had brought for him. He should then quickly return to his home as his kinsfolk were in much anxiety about him.

After he had bathed and eaten the celestial foods the Nāgas provided, Bhīma, dressed in white silks and gold ornaments, was led to the river. They entered with Bhīma and within moments they brought him out of the water near the place where he had been pushed in. Filled with wonder, Bhīma ran back to Hastināpura.

In the city Kuntī saw her sons arrive back without Bhīma. The other princes were surprised that he was not already there. They had assumed he must have gone ahead without them. Duryodhana and Dushashana feigned concern, but secretly they rejoiced, thinking Bhīma to be dead.

The virtuous-minded Yudhiṣṭhira believed that others were as honest as he was. Suspecting nothing, he told his mother, “We searched for Bhīma in the gardens and mansion for a long time. We went into the woods and called out for him. Finally we concluded he must have already left.”

Yudhiṣṭhira became fearful. Perhaps Bhīma had been killed. Kuntī shared his fears and she asked him again to go to the mansion with his brothers and search for the missing Bhīma. When her sons left, she summoned Vidura and said, “O wise one, I am afraid for Bhīma’s safety. He did not return with the others. I often see an evil look in Duryodhana’s eye. I know he is filled with malice toward Bhīma. Perhaps he has killed him.”

Kuntī hoped Vidura would give her solace. His words were always deeply considered and comforting. Vidura did not disappoint her. He replied, “Do not think in this way, O gentle lady. The great rishi Vyāsadeva has said that your sons will be long-lived. His words can never be false. Nor indeed can those of the gods, who have predicted a great future for your sons.”

Still, Vidura remembered the omens surrounding Duryodhana’s birth. He warned Kuntī to be on her guard. The evil prince might try anything.

For eight days Kuntī and her sons waited anxiously for any news of Bhīma. Then early on the ninth day they saw him running toward them, his white silks flowing in the wind. He came straight to Kuntī and bowed at her feet. As he rose each of his brothers embraced him warmly. With tears of joy they eagerly asked where he had been.

Bhīma knew everything about the circumstances by which he had come to be in the river. When he had found himself bound with cords he had suspected the envious Duryodhana. Vāsuki had confirmed his suspicions. The Nāga king could see everything by virtue of his divine sight. Bhīma related the whole story to his brothers–how he had gone to the Nāga kingdom and been given the rasa. The brothers could understand that even though the Kauravas had plotted Bhīma’s death, somehow by the arrangement of Providence he had become most fortunate.

Yudhiṣṭhira was shocked to learn of his cousins’ antagonism. He considered the situation carefully. If their elders were informed of what had ocurred, then there would be open enmity between the princes. Duryodhana would certainly try to dispose of them as quickly as possible. And the Pāṇḍavas’ position was not strong. Their father was dead and Dhṛtarāṣṭra was the king. He doted on Duryodhana and his other sons, and it was unlikely he would side against his own sons, to protect his nephews. Yudhiṣṭhira ordered his brothers to remain silent. They should tell no one about what had occurred.

Kuntī, however, confided in Vidura. He advised her to follow Yudhiṣṭhira’s suggestion. Thus the Pāṇḍavas said nothing, but from that day forward they became vigilant, always watching the Kauravas, especially Duryodhana and Dushashana.

Besides Gandhari’s one hundred sons, Dhṛtarāṣṭra had conceived another son by a servant maid who had waited on him during his wife’s lengthy pregnancy. Unlike his half-brothers, this boy, Yuyutsu, felt no envy or antagonism toward the Pāṇḍavas. One day he secretly informed Yudhiṣṭhira that Duryodhana, who had been deeply disappointed to see that his plan to kill Bhīma had failed, had again cooked a large quantity of the deadly datura poison into Bhīma’s enormous meal.

Bhīma laughed when he heard the news. Having drunk the Nāgas’ celestial elixir, he had no fear of Duryodhana. He sat down before him and cheerfully consumed the entire quantity of poisoned food. Duryodhana was amazed to see that Bhīma was not in the least affected. He gazed at the Pandava with open hatred.

Although the Kaurava princes detested the Pāṇḍavas, Bhīṣma and Vidura loved them and would spend much time with the five virtuous and gentle princes. Bhīṣma had been especially fatherly toward them since the time they had arrived from the forest. He had been fond of Pandu; now he felt the same fondness for Pandu’s sons. The boys reciprocated his love, and served him in various ways.

Reference:-https://vedabase.io/en/library/mbk/1/4/